Update: 3:42 p.m., July 13, 2015

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft has already resolved one of the key debates about Pluto: how big is it? The dwarf planet is 1,473 miles (2,370 kilometers) in diameter, slightly larger than scientists thought. Pluto is now confirmed to be the largest known object beyond the orbit of Neptune, in our solar system.

Original Post:

Tomorrow morning, if all goes according to plan, an unmanned NASA spacecraft called New Horizons will finally reach Pluto, snapping the first close-up photos ever taken of our solar system’s most famous dwarf planet.

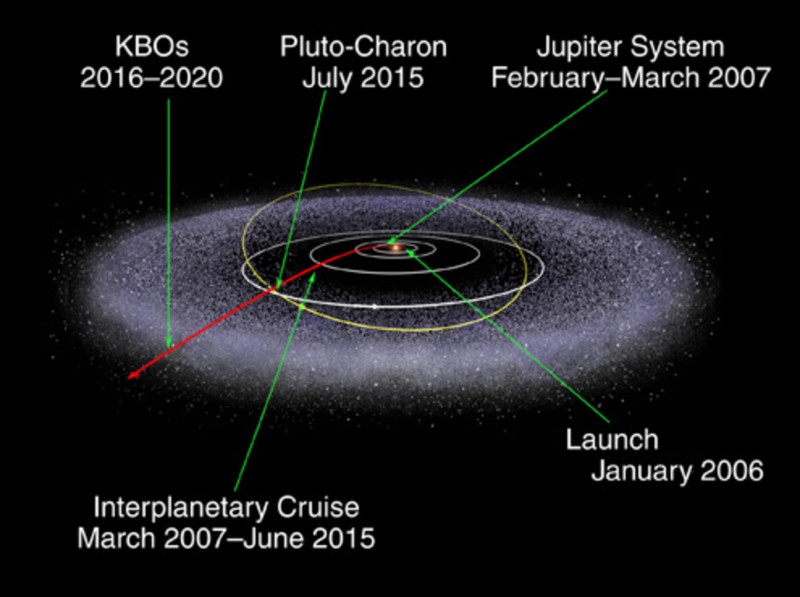

New Horizons launched in 2006; eight hours later it passed the moon. It took nine-and-a-half years to get to Pluto.

“In some sense, this is the bookend to the first, great, 50 years of space exploration,” says Jeff Moore, a research scientist at NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View. Moore leads New Horizon’s Geology and Geophysics Investigation Team.

It was almost exactly 50 years ago that we saw our first crisp images of a planet other than Earth.

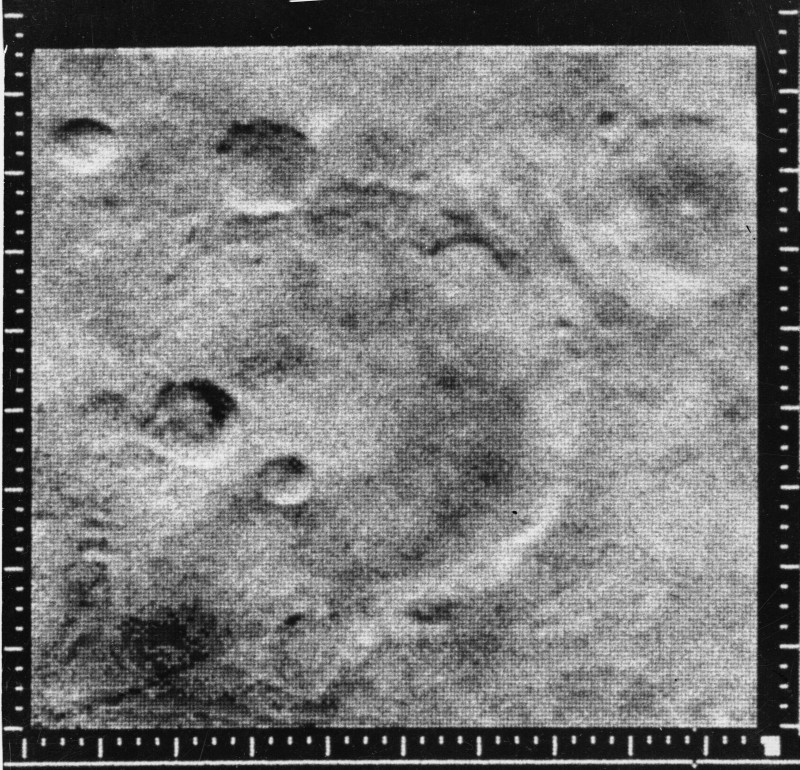

In 1965, Mariner 4, a NASA spacecraft the size of a Winnebago, whizzed past Mars, taking pictures along the way.

TV networks brought the news to American living rooms, disappointing some who’d hoped to catch a glimpse of alien life.

“The pictures and data recorded by Mariner 4 reveal Mars to be a cold, barren planet,” read the broadcaster from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

In 1974 Venus and Mercury got their close ups, thanks to NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft.

In the late 1970s and 80s, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 beamed back images of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

One by one, the planets in our solar system snapped into focus, thanks to cameras and transmitters launched into space.

Only Pluto, discovered in 1930 by the American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, remained largely unseen — and for good reason. Mars is about 50 million miles away. Pluto is four billion.

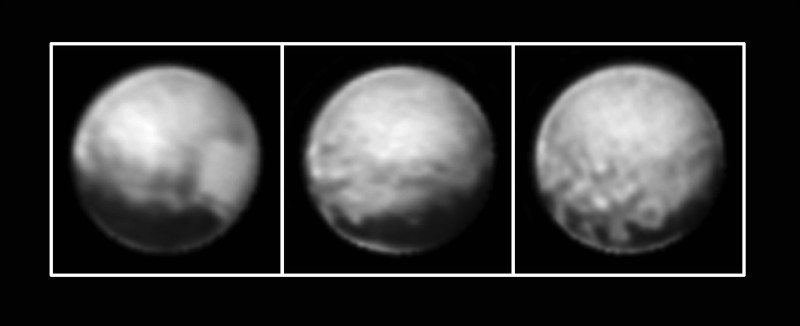

“Nobody knows what it looks like. That’s the whole point,” Moore says.

On Tuesday, the New Horizons spacecraft will pass within 8,000 miles of Pluto — the distance from San Francisco to Cairo. Once the highest-resolution images come in, we’ll be able to see objects the size of an office building.

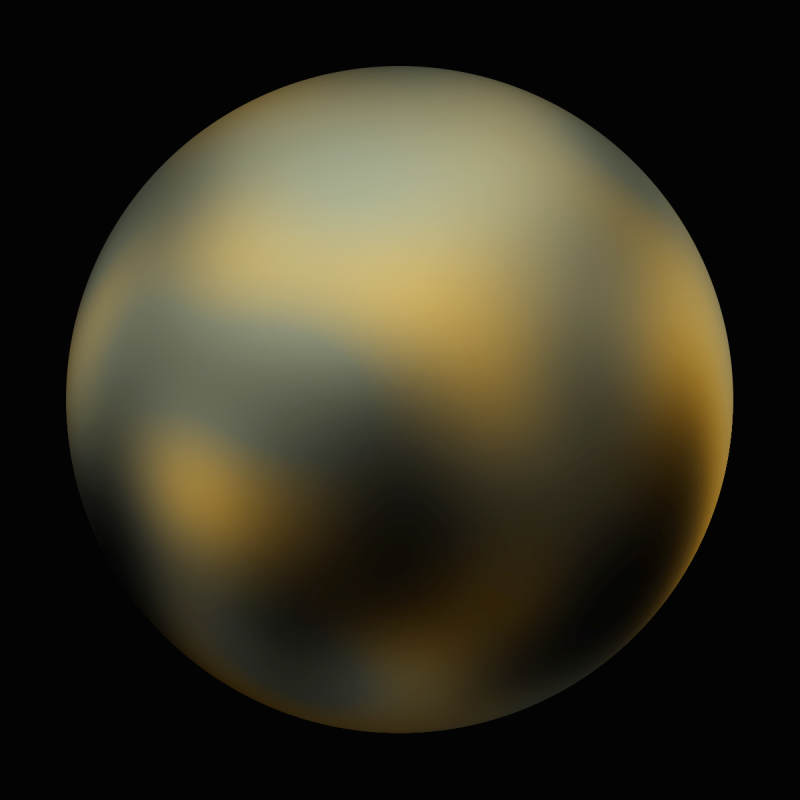

For Moore, it could be a revelation. Until now, the only images he’s seen of Pluto are distant and fuzzy. The dwarf planet looks like a moldy orange, with strange contrasting patches.

“Some of the patches on Pluto are as bright as new-fallen snow, some of the other patches are as dark as charcoal,” Moore says.

Scientists think those dark patches are methane, frozen into rock by Pluto’s minus-300-degree-Fahrenheit chill.

Moore will also be looking for signs of volcanoes on Pluto: “cryovolcanoes” that spew methane rocks and ice, rather than lava.

Moore wonders whether we might even glimpse riverbeds.

Not water rivers, like on Earth — Pluto’s much too cold for that — but rivers made out of an element with a much lower freezing point.

“Maybe neon,” Moore says. “So if we see riverbeds on Pluto they’d have to be carved by liquid neon.”

Riverbeds of neon. That’s the kind of planetary weirdness that will have Moore glued to his computer screen tomorrow morning.

Meanwhile, Mark Showalter, another Bay Area scientist on the New Horizons team, will be breathing a sigh of relief.

In 2011 and 12, Showalter, an astronomer at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, discovered or helped discover two of Pluto’s five moons: Kerberos and Styx.

Today, he’s a member of the New Horizons’ Hazard Analysis Team.

“My job in hazard analysis has been to analyze the data,” Showalter says, “just looking for anything that might be in the way. Any rocky shoals, if you will.”

Pluto is located at the inner edge of the Kuiper belt, a massive band of icy asteroids. From Showalter’s standpoint, it’s like a mine field.

After all, New Horizons is traveling at nine miles per second. That’s about 32,000 miles per hour.

“Way faster than a bullet,” Showalter says.

At that speed, collision with an asteroid as small as a BB pellet or a grain of sand could be disastrous.

“If we’re just unlucky,” Showalter says, “and that BB or grain of sand happens to sever a critical cable between two components, we could conceivably just lose all contact with the spacecraft.”

After a decade of waiting, a $700 million NASA mission would be lost.

“These are the kinds of things we fear most,” he says.

If Showalter and his colleagues spot an asteroid up ahead, they can steer New Horizons around it, a bit like an exceptionally long-distance video game. At this point, New Horizons is so far away that it takes hours for instructions to reach it, or for data to come back showing where, precisely, the spacecraft is.

Basically, Showalter says, “we’re playing dodge ball with a six-hour delay.”

That delay means the first photos of Pluto won’t start trickling in until Wednesday morning. The highest-resolution photos will arrive in the fall.

After its Pluto encounter, New Horizons will keep traveling, maybe for a decade, powered by plutonium pellets and, hopefully, sending back more photos from the icy edge of our solar system.