New observations of Saturn’s largest satellite, Titan, by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, paint a fresh picture of the striking similarities between the cold, distant moon and the Earth.

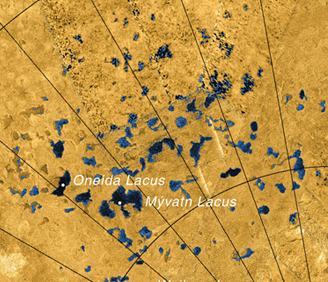

Mysterious, round-edged lakes filling depressions with no apparent sources of liquid have been found in the wide, flat plains in Titan’s polar region.

Titan is one of the most fascinating and enigmatic natural satellites in the solar system.

Its cold, dense nitrogen atmosphere is stocked with thick layers of hydrocarbon clouds, and an apparent liquid cycle of methane and ethane that parallels the precipitation, runoff, and formation of lakes and seas in Earth’s water cycle.

The vast lakes and small seas that Cassini introduced us to years ago, which are hundreds of miles across and possibly hundreds of feet deep, are supplied by an obvious source: extensive river networks collecting the runoff from precipitation falling on higher ground.

But the newly discovered family of small, rounded lakes set in the wide, flat polar plains and mostly unconnected to runoff channels has prompted scientists to refine our understanding of some of the processes that shape Titan’s surface.

How these lakes are filled is only part of the mystery. It is believed that, in the absence of runoff channels feeding them, these depressions likely collect liquid directly from precipitation, and possibly from underground sources.

On Earth, Crater Lake in Oregon is an example of a lake filled solely by rain and snowfall.

The other part of the puzzle is what made the depressions in the first place. Were they gouged out of the flat Titanian plains by meteorite impacts? Such crater lakes can be found on Earth, like Lake Ejagham in the Southwest Province of Cameroon, a circular, half-mile wide water-filled depression in a flat forest basin.

However, the structure and appearance of the strange lakes on Titan appear to be more similar to limestone cave and sinkhole formations on Earth, which are created when soft limestone and gypsum rock is dissolved by the action of water.

On Earth, such formations are most prevalent in humid and rainy climates. Numerous large sinkholes, or “cenotes,” are found in the jungles of the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico.

On Titan, these lake depressions are located in the relatively rainy polar plains, and are not to be found in the equatorial regions where there is considerably less rainfall.

A team of scientists calculated how long it would take for the alleged polar sinkhole depressions to form, taking into account the differences in conditions between Earth and Titan, including the nature of the frigid liquid hydrocarbons and Titan’s much longer seasons.

Titan’s seasonal cycle, which drives the rainy and dry periods that alternately fill and dry up the polar lakes, is tied in with the orbital period of Saturn and its moons around the sun, which is almost 30 years in length.

The science team estimated that a 300-foot-deep depression–created from the dissolving of surface rock by liquid hydrocarbon action–would take about 50 million years to form.

This may sound like a long time, but in terms of geologic change is not all that long. Titan’s surface in general is regarded as relatively “young” in the geologic timescale: about a billion years.

Though Titan’s surface is extremely cold—a couple hundred degrees below zero, cold enough that the burner on a gas stove would spew out liquid methane instead of gas—the parallels to conditions on Earth and landscapes that we might find familiar make this world great food for the imagination, and fuel for scientific curiosity.