As soon as NASA announced finding evidence of liquid water on Mars last month, speculation erupted that scientists may be able to answer the age-old question: Is there life on Mars?

Technically, we already know the answer.

“The answer is, ‘Yes,’ and it’s probably our own life,” says David J. Smith, a scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View.

Here on Earth, bacteria cover every surface we touch. And despite efforts to keep spacecraft as clean as possible, bacteria have likely hitchhiked all the way to Mars on NASA missions. Bacterial contamination was detected on the rovers that have driven across the red Martian desert.

Listen to the story:

These microbial travelers pose a big problem.

If a robot or astronaut drills into the Mars surface, testing for life, the Earth bacteria could get in the way, contaminating those tests.

“So we want to make sure that it is, in fact, Martian life that we find, potentially, and not just Earth contamination,” Smith says. “That would be a major bummer.”

Extreme Microbes

The Mars environment has a kind of biohazard safeguard already built in: it’s not a comfortable environment for most Earth bacteria to live in.

“It’s just not a nice place,” Smith says. “It’s extremely dry. Very cold.”

And with little atmosphere surrounding it, the surface of the planet is blasted with ultraviolet radiation. Most Earth microbes couldn’t hack it in those conditions. But Smith studies one that may have what it takes.

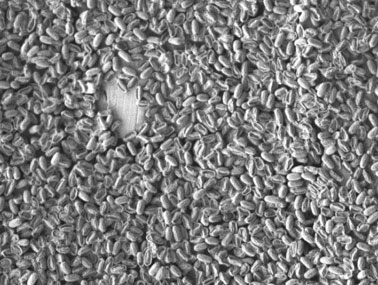

“The bacteria is called Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032,” he says. “That’s a mouthful.”

To endure extreme conditions, it forms a spore, essentially hunkering down in a biological fortress.

“In a sense, it’s like hibernation for bacteria,” Smith says. When it finds food or water again, it wakes back up.

This super-tough strain was found on a NASA spacecraft as it was being built inside a clean room, a place that’s meant to be mostly bacteria-free.

But how would the microbe fare if it got out on the Martian surface? Studying it there isn’t really possible. So, Smith is doing the next best thing.

Bacteria Take Flight

Twenty-three miles above Earth, at the very top of our atmosphere, it’s a lot like Mars: cold, dry and bombarded with UV radiation from the sun.

In early October, Smith and his colleagues launched millions of Bacillus pumilus bacteria to that altitude on a special ride.

A massive helium balloon, almost 1,000 feet tall, carried the bacteria in a miniature laboratory underneath it. The project is called E-MIST (Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere).

High above the Earth, the bacteria hung out for eight hours in the thin air and intense sunlight—conditions a lot like Mars.

Then, the balloon popped, sending them back to Earth on a parachute.

The bacterial samples were then picked up in Texas. Smith will be looking to see if they’re still alive and growing.

“It wouldn’t surprise me,” he says. “The adaptability and persistence of bacteria is consistently impressive.”

Planetary Protector

“The more we learn about Earth life, the more we realize it’s actually likely that Earth organisms could live on Mars,” says Catharine Conley, NASA’s Planetary Protection Officer. Her job, in essence, is protecting Mars from us.

Just as soon the liquid water announcement was made, NASA’s planetary protection policies were called into play, something that’s governed by international treaty.

NASA’s Curiosity rover is currently on Mars, driving around not far from the discovery site. But if the car-sized rover went to investigate, it would bring along Earth bacteria.

“It’s possible that there’s some kind sub-surface aquifer on Mars that we didn’t expect,” Conley says. “And so it would be equally foolish to go and introduce Earth organisms.”

On NASA’s 1975 Viking missions to Mars, the spacecraft were sterilized to kill off bacterial life.

“The spacecraft were designed to tolerate heat treatment – being baked above the boiling point of water for several days,” Conley says. “It didn’t quite kill off all of the organisms on the surface of the spacecraft, but it killed off the majority of them.”

But heat treatment is extremely expensive. So, areas of Mars that were seen as more hospitable to life were protected as “special regions.” Missions landing outside those regions could have higher levels of microbial contamination.

“This was a compromise,” says Conley. “Because as we keep exploring Mars, we discover that more of Mars is actually ‘special.’ And so we actually should be more careful than we have been being.”

Conley adds that understanding the resilience of Earth microbes will help inform NASA’s efforts to come. It may be that allowing spacecraft to “cure” on Mars, sitting in the intense UV light long enough, would be adequate to kill off even the hardiest Earth bacteria.

“This is the first time that humans as a species have had the chance to really explore carefully,” she says.

Humans don’t have a great track record of that. In the name of exploration, we’ve spread invasive species and diseases around our own planet. The hope is not to repeat that on other planets.

“We haven’t made any mistakes yet,” Conley says. “I really hope that we won’t do it while I’m in this job.”

Protecting Mars will only get tougher once humans start walking on the red planet. NASA is planning to make that happen in about twenty years.