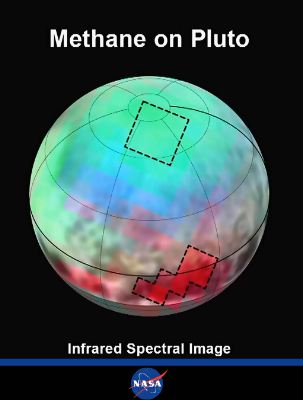

NASA has just released the first high resolution images from the New Horizons’ close encounter with Pluto, along with a few of the exciting discoveries made in the 24 hours since the probe first phoned home.

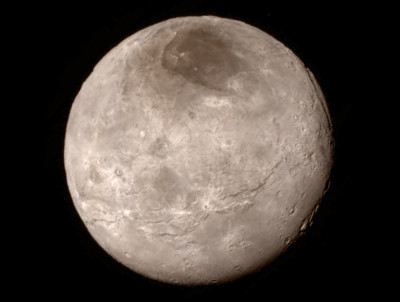

A few of the discoveries include: a canyon on Charon that is 4 to 6 miles deep (3.5-5 times deeper than our own Grand Canyon), an 11,000-foot mountain range near Pluto’s equator and a region of Pluto’s surface so young that it does not yet have any impact craters. Now scientists need to figure out what could generate Pluto’s mountains, since the dwarf planet isn’t heated by gravitational interactions with a larger body.

“This may cause us to rethink what powers geological activity on many other icy worlds,” says New Horizons’ Geology, Geophysics and Imaging deputy team leader John Spencer, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Mark Showalter has been studying our solar system for over 30 years, but he says that this week’s Pluto flyby is the single most exciting thing he’s ever been involved in.

“Pluto has not disappointed us one bit. It is an utterly fascinating world, and everybody will appreciate it for that very, very soon.”

Earlier this week, we spoke with Showalter, an astronomer at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, about how his hazard analyses helped keep the New Horizons spacecraft out of harm’s way.

Now the flyby is over and the first photos are in. We reached Showalter at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

So, are you drinking champagne yet?

Mark Showalter: [laughs] There was some celebration last night, that’s for sure. But now most of us are back to work. Certainly, the best data that we’ve seen so far has just come down overnight.

When did you get confirmation that it all worked?

We were watching as the operation center first got a signal lock at 8:54 pm roughly last night. Signal lock, for me as somebody who works on hazard, is the best piece of news whatsoever. It just means that there is a signal coming down from the spacecraft. Then, over the next minute or two, we had confirmation that the temperature was right and that the solid-state recorder, which is basically the storage disk that saves all the data, had the right amount of data on it. So essentially, we went step by step down the list of things that might have gone wrong, and everything was reported to be nominal, which in mission-speak means good. So we had a successful flyby and when we knew that, there was a huge celebration.

How did it all go? Were there any surprises that had you at the edge of your seat?

Actually, what was delightful was that there were no surprises whatsoever. That’s the point in time when you absolutely do not want any surprises at all! Since I’ve been particularly focused on the hazard analysis, it was a huge relief for me to know that the spacecraft was safe. And I gotta say that even though we thought the chance of damage was something like 1 in 10,000, we all know that things can go wrong. Anything that’s built by human hands sometimes fails us, and this was a space craft that was making its most important observations ever for essentially a 9-hour period without any contact whatsoever from Earth. So just knowing, finally at the end of all of that, that it had completed its set of observations successfully and was still healthy… You can’t imagine how relieved we all felt!

How long will we have to wait to see the rest of the data?

Actually, it will be 16 months to get the last Pluto data down off the spacecraft. The reason is that the antenna is not that big, and the whole spacecraft only has about 200 watts of power, not all of which can be used to power the transmitter. So, we’re essentially getting data down at something on the order of kilobits per second. That’s a very slow rate: slower than any dialup modem you might ever remember using. So it’s just going to take a while, and we’re going to take down every bit of data that we obtained during the Pluto flyby.